take your pencil for a walk on the wild side

What's the point of doing wildlife art when you can just point your gazillion mm Cannon (or Nikon or Pentax) at that squirrel, deer or snow leopard and fire away? I like cameras, they're fast, accurate and portable. I use them a lot for shooting reference or recording adventures on video.

Wait... snow leopard?

Scientists are like detectives: they follow trails, look at tracks, habitat, poop, and prey remains. They use mountaineering gear, mountain climbing skills, extreme weather camping gear, camera traps, radio collaring, specially trained poop-sniffing dogs. They buy plane tickets. The get visas, passports, innoculations for exotic diseases. They hire Sherpas, yaks, buy food at the local market. Hopefully they get some grants to pay for it all. They learn quite a lot, including that the snow leopard likes to eat Siberian ibex, argali sheep, chukar partridge, and any domestic critter dumb enough to get close. Getting a picture of behavior they know happens, like a leopard leaping on an ibex on a snowy ledge, would be next to impossible.

Doing a painting of it is much easier. And the artist doesn't have to lug 100 pounds of camera gear up the Tost Mountains in outer Mongolia (the artist actually has no clue where that is), the artist can sit comfortably on a portable stool at the zoo, or google stuff online. ...and... IT'S FUN!

Pencils and journals fit in epic quest backpacks. My cousin is a PhD bearing entomologist. She does field studies in Tennessee which require lengthy hikes up stream beds (there are no other trails) full of slimy mossy rocks carrying a 150 pound back pack. There isn't much room in there for camera gear. A notebook and a pencil are something else.

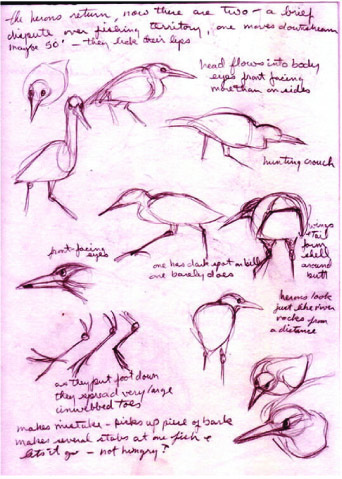

Drawing what you see makes you see it better. The pencil also makes you truly observe, very closely, what you are drawing. You are there, in the moment, deeply experiencing what's there.

Nature Journals show climate and habitat change. Even journals kept by amateur observers or kids can be useful to scientists. If you've doodled the first robin of spring each year, and shown when and where he shows up, what habitat he's living in, what he's eating, someone reading your journal can see the changes in habitat, migration patterns and climate over the years.

Captain's Log; Stardate 201303... it worked for Captain Kirk, it worked for sea captains for thousands of years, and for modern pilots; keeping a log, or personal journal of your adventures helps you remember them, is a great thing to share with your friends, your relatives, and your descendants centuries from now, and...

IT'S FUN!

Photos lie. Have you ever had someone take a really really baaaaad picture of you? One you'd never put on facebook or tumblr? Yup! And then somebody else, on the exact same day, takes a really great picture of you where you look like a star! Lighting, angle, movement, your expression, how good the photographer is, all that makes a photo great or awful. There are places where wildlife art is more effective than photos. I like my Peterson's field guides, illustrated with highly detailed paintings. Photos can lie, have shadows that obscure detail, be taken from an angle that doesn't show the critter to its best advantage. An illustration is the ideal picture of that critter. And IT'S FUN!

Your $200 million movie. You want to do a kids' book about a family exploring a winter wood in Vermont, looking for animals and their tracks and signs.You could find some people to play the family, which means hiring actors (or possibly shanghaiing your relatives into posing), you have to get costumes/clothing that they'd wear in the story, you'd have to get some good camera gear, lights, backpacks to carry it all, maybe some sherpas, or a yak, or sled dogs. Then you'd have to go to Vermont. Not bad if you live in New York, but if you are writing this book from southern California, that's a big plane ticket...

...especially for the sled dogs. Then you have to find the animals. Are you going to hire an animal trainer, like they do in movies, to have the animals pose for photos? Arrrrggghhhh! To do the book with photos, you have to become a movie director!

One artist, with some good reference material (and possibly one little trip to Vermont) can DRAW & PAINT the entire book much faster and cheaper. And... IT'S FUN!

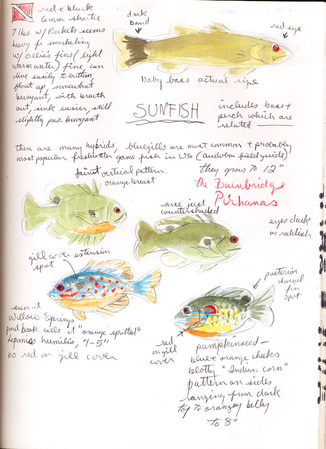

But I don't have an underwater camera! When I was scuba diving, I couldn't afford an underwater camera. I saw a lot of really cool stuff, even in the coldwater quarries and lakes where we did most of our diving. We all carried dive slates (a piece of stiff plastic) to write messages to our buddies (you can't talk underwater, except Sign Language). I could also sketch what I saw on the dive slate. One summer at Assateague & Chincoteague Islands, VA, I sketched the fish I saw in the eelgrass beds off the west side of Chincoteague Island. I wrote descriptions of color and behavior. Later, I redrew them in my sketchbook, and watercolored them. Then I went to the visitor's center on Assateague and talked to a ranger/naturalist. She identified the fish. The best one was a little black squiggle, the size of a tadpole. I'd seen him on the bottom, in a shallow bowl of sand, darting out as if he was hunting, then darting back to the center of his bowl. The naturalist looked at the sketch and said "baby sea bass, hunting amphipods". My observations and notes were enough to identify what was, for me, a mystery beast.

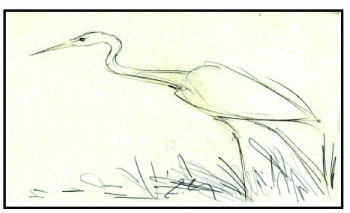

Or a zoom lens the size of the Hubble telescope. I'd love to have one of those $3000 cameras with the zoom lens the size of a NASA telescope. I need to replace my van first. And pay bills. And feed the dogs. So if I go on a hike and see a bird out in the marsh, my pretty good Nikon Coolpix will see a bird of indeterminant species. My binoculars will see a snowy egret. And I can draw that. You can take your sketchbook and pencil (and maybe a small pan of watercolors, or colored pencils) to the zoo, the aquarium, on that camping trip, the beach, on a dive. And... IT'S FUN!

Wait... snow leopard?

Scientists are like detectives: they follow trails, look at tracks, habitat, poop, and prey remains. They use mountaineering gear, mountain climbing skills, extreme weather camping gear, camera traps, radio collaring, specially trained poop-sniffing dogs. They buy plane tickets. The get visas, passports, innoculations for exotic diseases. They hire Sherpas, yaks, buy food at the local market. Hopefully they get some grants to pay for it all. They learn quite a lot, including that the snow leopard likes to eat Siberian ibex, argali sheep, chukar partridge, and any domestic critter dumb enough to get close. Getting a picture of behavior they know happens, like a leopard leaping on an ibex on a snowy ledge, would be next to impossible.

Doing a painting of it is much easier. And the artist doesn't have to lug 100 pounds of camera gear up the Tost Mountains in outer Mongolia (the artist actually has no clue where that is), the artist can sit comfortably on a portable stool at the zoo, or google stuff online. ...and... IT'S FUN!

Pencils and journals fit in epic quest backpacks. My cousin is a PhD bearing entomologist. She does field studies in Tennessee which require lengthy hikes up stream beds (there are no other trails) full of slimy mossy rocks carrying a 150 pound back pack. There isn't much room in there for camera gear. A notebook and a pencil are something else.

Drawing what you see makes you see it better. The pencil also makes you truly observe, very closely, what you are drawing. You are there, in the moment, deeply experiencing what's there.

Nature Journals show climate and habitat change. Even journals kept by amateur observers or kids can be useful to scientists. If you've doodled the first robin of spring each year, and shown when and where he shows up, what habitat he's living in, what he's eating, someone reading your journal can see the changes in habitat, migration patterns and climate over the years.

Captain's Log; Stardate 201303... it worked for Captain Kirk, it worked for sea captains for thousands of years, and for modern pilots; keeping a log, or personal journal of your adventures helps you remember them, is a great thing to share with your friends, your relatives, and your descendants centuries from now, and...

IT'S FUN!

Photos lie. Have you ever had someone take a really really baaaaad picture of you? One you'd never put on facebook or tumblr? Yup! And then somebody else, on the exact same day, takes a really great picture of you where you look like a star! Lighting, angle, movement, your expression, how good the photographer is, all that makes a photo great or awful. There are places where wildlife art is more effective than photos. I like my Peterson's field guides, illustrated with highly detailed paintings. Photos can lie, have shadows that obscure detail, be taken from an angle that doesn't show the critter to its best advantage. An illustration is the ideal picture of that critter. And IT'S FUN!

Your $200 million movie. You want to do a kids' book about a family exploring a winter wood in Vermont, looking for animals and their tracks and signs.You could find some people to play the family, which means hiring actors (or possibly shanghaiing your relatives into posing), you have to get costumes/clothing that they'd wear in the story, you'd have to get some good camera gear, lights, backpacks to carry it all, maybe some sherpas, or a yak, or sled dogs. Then you'd have to go to Vermont. Not bad if you live in New York, but if you are writing this book from southern California, that's a big plane ticket...

...especially for the sled dogs. Then you have to find the animals. Are you going to hire an animal trainer, like they do in movies, to have the animals pose for photos? Arrrrggghhhh! To do the book with photos, you have to become a movie director!

One artist, with some good reference material (and possibly one little trip to Vermont) can DRAW & PAINT the entire book much faster and cheaper. And... IT'S FUN!

But I don't have an underwater camera! When I was scuba diving, I couldn't afford an underwater camera. I saw a lot of really cool stuff, even in the coldwater quarries and lakes where we did most of our diving. We all carried dive slates (a piece of stiff plastic) to write messages to our buddies (you can't talk underwater, except Sign Language). I could also sketch what I saw on the dive slate. One summer at Assateague & Chincoteague Islands, VA, I sketched the fish I saw in the eelgrass beds off the west side of Chincoteague Island. I wrote descriptions of color and behavior. Later, I redrew them in my sketchbook, and watercolored them. Then I went to the visitor's center on Assateague and talked to a ranger/naturalist. She identified the fish. The best one was a little black squiggle, the size of a tadpole. I'd seen him on the bottom, in a shallow bowl of sand, darting out as if he was hunting, then darting back to the center of his bowl. The naturalist looked at the sketch and said "baby sea bass, hunting amphipods". My observations and notes were enough to identify what was, for me, a mystery beast.

Or a zoom lens the size of the Hubble telescope. I'd love to have one of those $3000 cameras with the zoom lens the size of a NASA telescope. I need to replace my van first. And pay bills. And feed the dogs. So if I go on a hike and see a bird out in the marsh, my pretty good Nikon Coolpix will see a bird of indeterminant species. My binoculars will see a snowy egret. And I can draw that. You can take your sketchbook and pencil (and maybe a small pan of watercolors, or colored pencils) to the zoo, the aquarium, on that camping trip, the beach, on a dive. And... IT'S FUN!

So, what's the best animated movie you've seen, with animals in it?

Are you Frozen? Look UP! Also look at the rest of Pixar's films, and Disney and Dreamworks, and Hiyao Miyasaki (Studio Ghibli) and WETA (those New Zealand geniuses who gave us Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, and Narnia, and the CG critters that looked totally real). Look at any great animated film you've seen. Do you think those animators and designers just sat down at their drawing boards and drew Melman the Giraffe (Madagascar) from memory? "Oooooo, I saw a giraffe on Animal Planet once, I'll just design one from that."

Um, no. Your memory is stupid, It's thinking about that Ben and Jerry's Chunky Monkey you had last night and wishing you'd get more. "Giraffe" wasn't all that important, so it didn't store that very well. (OK, there is the odd super gifted person who can recreate the entire New York skyline from memory, or maybe three escaped zoo animals who can make a mud model of the same, but you aren't them). If you are designing Melman the Giraffe, you are looking at photos of giraffes, at youtube videos of giraffes, at nature specials, at Animal Planet till your eyes bleed, you are visiting the zoo until every keeper knows you by name, and maybe you booked at least one flight to Africa. You are still doing a cartoon, so you exaggerate stuff, you stylize stuff, you anthropomorphize, but beneath all that, Melman is still a giraffe, and when he runs with his buddies to catch the circus train in Madagascar 3, he has that wonderfully odd long-leggity lopey slow motion gallop that only giraffes have. And the zebra, Marty, is galloping like a zebra, because another animator studied equines of all stripes.

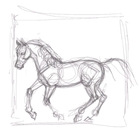

Have you driven a Fjord lately? Or a reindeer? Or trained a dragon? Or ridden a macawnivore? For Frozen, Disney animators didn't just throw in a cute Bambi clone (Bambi is a Roe Deer, from the British Isles, Sven in Frozen is a reindeer from Scandinavia). They studied domesticated reindeer and their very close wild relatives caribou. They noted their various colors (from pale to dark), that girls have antlers too, the really big snowshoe feet that leave a circular print and allow the reindeer to run efficiently on snow. And that reindeer are very good swimmers (they cross rivers in their migrations), so when Sven falls into the fjord, he can swim to safety. They did some exaggerating, stylizing and anthropomorphizing too: Sven's eyes are on the front of his head (hoofed animals are prey, and have their eyes on the sides of their heads so they can see the wolfpack coming)... and his eyes look kind of like humans', so he can have expressions most of the audience understand better. He also has antlers. The story takes place in summer (which Elsa turns into winter), so Sven's antlers would be small and covered in velvet, until winter. Well, maybe Elsa's winter magic made his antlers grow instantly. Anyway, it looked cool on film. And Sven's spraddley reindeer gallop was somewhat different from how a horse gallops.

The artists needed some horses for the heroes, and villains to ride, but they didn't pick just any horse out of their imagination. They found that in Scandinavia (especially in Norway) there is a very old breed (more than 4000 years old) of horse which is adapted to the harsh climate of the north: the Fjord. It is a small, sturdy horse, strong and agile, and able to carry a big person. Fjords come in one color: dun. Well, actually they come in five shades of dun (and the odd white). Dun ranges from sand to gold to cream to pewter to silver, always with darker points (mane, tail, lower legs)(and sometimes a dorsal stripe, a transverse stripe over the shoulders, and zebra strips on the upper legs). Fjords have a unique and pretty mane: white on the outside, with a dark stripe down the center. Their manes are cut short to show off this color, and sometimes the white and black parts are trimmed in patterns like hearts or crenelations ( notches found at the top of castle walls). The animators used this in the film to good effect: Hans' horse is "brunblakk", the golden dun most often seen in the breed. Anna's horse (which spooks, dumps her in the snow and runs back to the castle) is a light "gra", or grulla (a pewter/silver color... not grey, grey is made up of white and dark hairs mixed, and there are no greys in the Fjord breed. In grulla, each hair is silver). Fjords all look very much alike, and there are no black or bay or chestnut, or pinto horses or horses with white socks... but the artists understood how to make each horse look different, and yet tell the truth. Some of the details of animal behavior were wonderful too: Anna's horse spooking and dumping her was typical of a large prey item (I've been dumped by terrified horses a few times). And the way Anna's horse trudged through the deep snow was exactly how horses move (they are heavier than reindeer or sled dogs and sink in more, and sort of lurch like a boat on heavy seas).

Fantastic creatures: In How To Train Your Dragon, the dragons are fantastic creatures of the imagination (if you're drawing dinosaurs, you have science and bones to work with), the dragons are based on real animals, from big black cats to lizards to birds to dinosaurs. For the Croods, the animators had to also come up with fantastic creatures (the real Ice Age animals had already been used up by those Ice Age films). They studied real animals, and combined them in fun and interesting ways.

Big Sciencey Word Time:

anthropomorphize...anthropomorphization... anthropomorphizing: anthro = human, morph = shape, giving human shape, or characteristics to something else, like an animal. Marty, Melman and all their friends in Madagascar are anthropomorphized animals. They talk (though humans can't understand them, this makes the story a little more believable), they drive cars (silly, but funny, and "only humans and penguins can drive" accdording to Alex... Marty disproves this nicely), and they sometimes stand on two legs (easy for penguins, who do that anyway, but really awfully odd for a zebra: it's hard for a horse to stand on two legs). Bugs Bunny, Wil E. Coyote, Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse are classic examples.

stylize... stylization... stylizing... style, your style, how you interpret what you see. It doesn't look like a photo. It might be a cartoon, or an illustration in a kids' book that is sort of realistic, but not entirely. The animals in the Narnia or Hobbit films are realistic, photo-realistic,, utterly real looking. The ones in Madagascar, or most Disney or Pixar films are stylized.

You have to understand reality before you can bend it. How to Train Your Dragon was one awesome little film. Those of us who have lived in the Viking Age (at least on the odd weekend, as historical reinactors) were amused by the Vikings: it was clear the animators had studied the Viking Age, absorbed its style, and then run off into outer space with it. Dragons? I wanted to say, "where'd you find the models?"

The same place Disney found the Lion King. The same way Pixar found Nemo, and where they were Brave with bears.

They found the dragons in the natural world. Toothless owes his design to a study of critters ranging from salamanders to big black panthers. The other dragons show hints of bird and reptile and mammal and dinosaur.

Go ahead, be creative, tell your own story, design your own characters and creatures. Make your own comic book. Do your own storyboards for your own film. Do a comic strip. A play. A book. But look at reality, and understand it, first.

|

Draw Like a Pro:

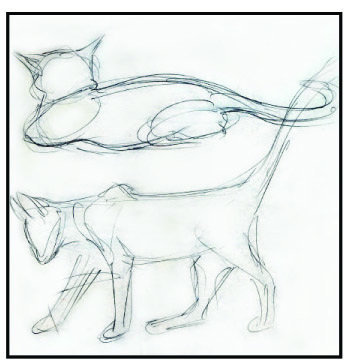

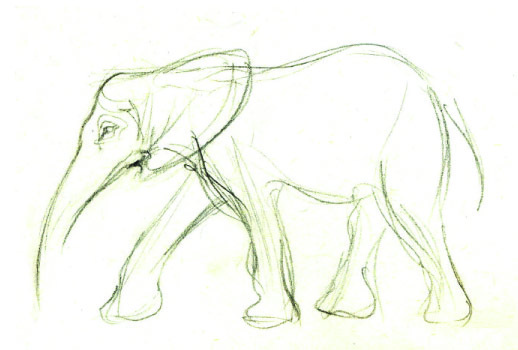

Draw like an animator: animators, especially those working on films using CG (computer generated imagery), start with the skeleton. They draw the bones, in correct proportions, with the joints in the right places (this is how they'll make the animal move later!). Then they add muscles, then skin, then fur or feathers or scales. Understanding the anatomy makes their creations more real, more believable. You can start with a stick figure to represent the bones. Use big basic shapes for muscles and body masses. Pay attention to the shape of fur tracts (how the fur or hair lays, what direction it goes, how long it is). Where are feathers or scales bigger or smaller? Why? Mouse Vision and Hawk vision: The first thing everyone does is take their pencil for a walk around the edge of whatever they're drawing. Nnnnnnnnnnnoooooooooooooooooooooooooooo!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! This is like a mouse exploring the edges of a sleeping elephant, and trying to draw a map of it. "Oooo, let's see, I'll just walk around this big flappy thing here (doodle doodle) and down this snakey thingie (doodle) and around this big treeish thing (scribble scribble) and past this wall, and there's this ropey looking thing and..." by the time he gets to the ropey looking thing his drawing is all out of proportion because he doesn't have the navigational instruments and skills that our ancestors had when they mapped places like the Chesapeake Bay (before Google Earth). And even some of their maps are a little out of whack. Now imagine you're a hawk, flying well above the sleeping elephant. You see the whole thing; a kind of big block of grey (because you're really high up and even you can't see any detail yet). That's what you'd draw first: the big blocky shape, real quick, sketchy, kind of mapping out that basic shape on your page. Then you fly closer, and see more detail; scribble that in, big eggy shape of belly, longish rectanlges of legs, triangle-ish flappy thing, squiggly ropey thing. Now you've got the PROPORTIONS right! Now you can fly closer and work on the details. Practice Practice Practice. Take your sketchbook along and just draw, a lot. Everywhere. Now look at the PDFs below for some more ideas. |

|

| ||||||||||||