Cape Henlopen and the Delaware Bay's Ancient Awesome Phenomenon

Each May, an ancient beast crawls up out of the shadowy depths. It's mission: to deposit eggs along the tide line, gazillions of pinhead sized green pearls. They have been doing this for about 450 million years, since the late Ordovician period, or at least, that's how old the oldest fossils are... that we've found so far. Life had crawled onto land (and left footprints) in the early Paleozoic (530 million years ago), but it was primitive stuff, with exoskeletons. Fish wouldn't grow legs and turn into amphibians until about 370 million years ago during the Devonian period. Meanwhile, why are horseshoe crabs climbing out of the water to lay eggs at the edge of the tide? To avoid sea-going predators?

Today, Limulus polyphemus (the Atlantic Horseshoe Crab) and its three relatives (in total, four species in the order Xiphosura, not crabs at all, but more closely related to arachnids) still come to the edge of the water in this ancient ritual.

Today, we have birds. Specifically, the Red Knot, whose life is intertwined with the horseshoe not-crab. This little sandpiper, the size of a robin, flies from the tip of South America to the Arctic to nest.

It...

does...

not...

stop...

...until it reaches the Delaware Bay, and the feast of Horseshoe eggs laid out for it. The Red Knot spends a week or so doubling its weight back to normal, and then flies on to the Arctic. The two species schedules come together for this critical moment in May... schedules affected by climate change and humans developing the very shorelines both species depend on.

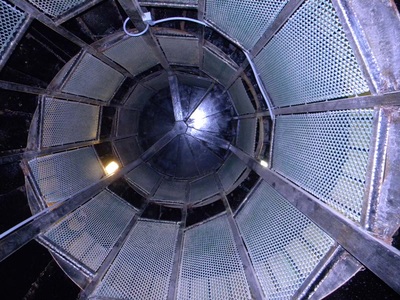

Fortunately, the Delaware Bay has sanctuaries and beaches devoted to the preservation of horseshoes and knots. You can go witness this spectacle first hand. The DuPont Nature Center is a great place to start. Work your way down the coast to Slaughter Beach, Fowler Beach, Prime Hook Beach, Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge, Broadkill Beach and Cape Henlopen State Park. The beaches are often neighborhoods, like Slaughter Beach, which take pride in caring for their horseshoe spawning beaches. Short lanes, marked with street signs mark where you can park and get to the beach down a short trail. The pavillion by the firehouse at Slaughter Beach has restrooms and shady picnic tables. Fowler Beach can only be accessed by a half mile hike from the parking lot. I visited it once years ago when you could still drive to the beach (you can see cars on the beach on google earth)... I turned to find the tide coming in over the road behind me, and drove past swimming horseshoe crabs. A bit not good. Cape Henlopen has a neat set of public programs, including one where you can sign up to help count the crabs coming ashore on the bayside of the cape. It also has nice swimming beaches. I wouldn't recommend swimming at Slaughter Beach, the horseshoes are wall to wall, and some of the ones that got stranded are dead and stinky. The beach is well worth a visit, and you can collect pretty bay pebbles and cobbles while there. Cape Henlopen has a wonderful campground (decadence! showers! water at each site!) shady pine trees abound, beach dunes, biking and hiking trails and WWII watchtowers which can be climbed.

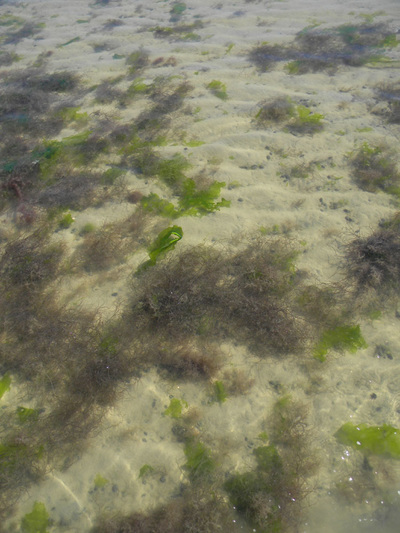

Here are some shots from the 2015 horseshoe crab spawning. I missed the red knots by about a week. But, plenty of crabs.

Today, Limulus polyphemus (the Atlantic Horseshoe Crab) and its three relatives (in total, four species in the order Xiphosura, not crabs at all, but more closely related to arachnids) still come to the edge of the water in this ancient ritual.

Today, we have birds. Specifically, the Red Knot, whose life is intertwined with the horseshoe not-crab. This little sandpiper, the size of a robin, flies from the tip of South America to the Arctic to nest.

It...

does...

not...

stop...

...until it reaches the Delaware Bay, and the feast of Horseshoe eggs laid out for it. The Red Knot spends a week or so doubling its weight back to normal, and then flies on to the Arctic. The two species schedules come together for this critical moment in May... schedules affected by climate change and humans developing the very shorelines both species depend on.

Fortunately, the Delaware Bay has sanctuaries and beaches devoted to the preservation of horseshoes and knots. You can go witness this spectacle first hand. The DuPont Nature Center is a great place to start. Work your way down the coast to Slaughter Beach, Fowler Beach, Prime Hook Beach, Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge, Broadkill Beach and Cape Henlopen State Park. The beaches are often neighborhoods, like Slaughter Beach, which take pride in caring for their horseshoe spawning beaches. Short lanes, marked with street signs mark where you can park and get to the beach down a short trail. The pavillion by the firehouse at Slaughter Beach has restrooms and shady picnic tables. Fowler Beach can only be accessed by a half mile hike from the parking lot. I visited it once years ago when you could still drive to the beach (you can see cars on the beach on google earth)... I turned to find the tide coming in over the road behind me, and drove past swimming horseshoe crabs. A bit not good. Cape Henlopen has a neat set of public programs, including one where you can sign up to help count the crabs coming ashore on the bayside of the cape. It also has nice swimming beaches. I wouldn't recommend swimming at Slaughter Beach, the horseshoes are wall to wall, and some of the ones that got stranded are dead and stinky. The beach is well worth a visit, and you can collect pretty bay pebbles and cobbles while there. Cape Henlopen has a wonderful campground (decadence! showers! water at each site!) shady pine trees abound, beach dunes, biking and hiking trails and WWII watchtowers which can be climbed.

Here are some shots from the 2015 horseshoe crab spawning. I missed the red knots by about a week. But, plenty of crabs.

just flip'em:

If you see a crab on the beach upside down, grab it gently by the edges of the main shell and turn it over... if it is very far up the beach, you can return it to the water (they are capable of keeping their book gills wet long enough to return on the next tide, usually). They can't hurt you, their little tweezer feet tickle and are only good for sifting food out of the bottom sediments and walking. The spikey tail is only for turning the crab over if it gets stuck, it is fragile and can't hurt you. Crabs will curl up if upside down out of the water, waving their tails (trying to turn over), in an attempt to keep their gills from drying out. Girls have tweezer feet in front, boys have boxing glove feet in front. They have more than two eyes and blue blood.

horseshoe spawn: bayside, Cape Henlopen

On the shallow bayside beaches, horseshoe crabs come in small groups (one female, several smaller males) or pairs. they prefer high tide, full or new moon (bigger tides) and darkness. I caught a few out earlier in the day, but our horseshoe crab count happened at nightfall. Here a couple of wandering kids check out the horseshoes. One points out that the tail isn't a weapon, it's a tool used to turn the crab over if it gets flipped. The tail is rather fragile, never pick up a crab by the tail, but by the edges.