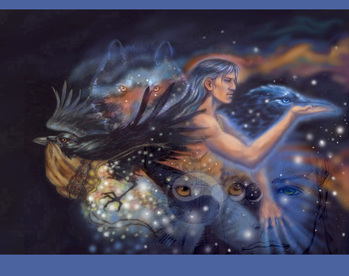

Raven and Wolf are connected in myth, and science; early human hunters observed ravens leading wolves to prey, and sharing in the feast. On Baffin Island, traditional hunters still speak to Raven, and follow the real birds to caribou herds and other prey. These real world observations led to many myths where Raven and Wolf walk side by side (Norse myth: Odin has two ravens, Thought and Memory, and two wolves who walk by his side).

Bran, Ravenkin, and Ian, whose "totem animal" is Wolf, work for the E.L.F. Bran pilots the E.L.F.'s aircraft (long ago he piloted privateers and Viking ships), Ian has a few skills unusual for a human. Both are on a mission of otter importance, until the quiet autumn riverbanks are invaded by a creeping evil...

(PG13ish, suitable for YA and older)

The creeping evil in this tale may be triggery to some. While this tale contains heroes and humor, and karmic justice, it is based on a true story: some years back a newspaper article told of the discovery of the mutilated body of a Black Lab, one that had gone missing from someone's yard... the crime was never solved. Those of us who love the other creatures of the Earth react like Ian, wishing there was far harsher justice than the minor fines usually levied if the crime is solved. This was my reaction to that story.

Following Raven

“Somebody lost their pack.” This spoken by a young man, earth brown hair streaked with yellow, like a wolf’s ruff. His leaf-green T-shirt with its

picture of a pack of wolves in full flight matched his eyes, intently studying a home-made poster.

The poster at the counter of the Turkey Hill Minute Mart showed a black Lab, grinning up at the photographer, amiably supporting a small child draped around his neck. The child may have been closer to strangling the dog than to hugging him, but the Lab’s expression showed that this was a puppy of his pack, one to be tolerated and protected. Above the picture, in bright crayon words written by an older child, was “I’m Buddy, help me find my way home”.

Ian’s empty hands were suddenly filled by three bottles of Gatorade, bright blue. “There is no blue food, you know,” he said to the man behind him. Ian set the Gatorade down on the counter, beside a couple of packs of trail mix, four chocolate bars, an orange juice and one green tea, no sugar.

One of the Gatorade bottles was retrieved, held up to the light. A man who might have been twenty-something, or forty-something, lean as a greyhound and taller than Ian contemplated the bottle, “Cerulean then. Yeah. No, wait. Ultramarine. Maybe Prussian.”

Ian’s face bore the same patient look the Lab in the photo.

“Anyway, what about blue jello, blue sno-cones, blue fruit roll-ups?”

“No real blue food.” Ian said.

“Blue berries. Blue mussels. Blue corn.” Bran thunked the blue stuff onto the counter by the register, grinning,“Best human invention since the X-Box. Except for this stuff.” He caught up the chocolate bars, “Thanks.”

“Don’t mention it.” Ian saw the eyes of the young woman behind the counter stray past him to Bran’s face, with its lines as clean as the sweep of flight feathers. Ian knew without looking, that face was breaking into a pirate grin. Counter Girl’s face melted into an appreciative smile. Her eyes drifted up to hair the color of storm clouds then landed in Bran’s mountain sky eyes. For a heartbeat hers registered something, as if she’d looked into the space between the stars and got vertigo.

“Water,” Ian said suddenly, elbowing Bran in the ribs.

“Oh...yeah.” Bran said.

Counter Girl blinked as if she was waking up and looked up at Ian. “That’ll be...” she started to say.

Bran started toward the coolers at the back of the store, “I’ll get it. The water.”

“Which means I pay.” Ian said to Bran’s retreating back.

A moment later Bran plunked four bottled waters onto the counter.

Ian studied the irony of the price sticker on the plastic one liter bottles, “even I remember when you didn’t have to pay for water. We got enough clean water in Pennsylvania to reintroduce river otters, but we still gotta buy water for ourselves...”

Bran didn’t answer, his eyes were fixed on the lost dog poster, swashbuckler smile gone.

“Bran?”

He started, a raven on roadkill who’s just avoided being flattened by a truck.

“Hey...”

“Let’s go.” Bran caught the plastic bag out of Counter Girl’s hand and strode toward the door.

Ian gave her an apologetic smile, took the change and trotted after him. “You saw something,” he said quietly when he had caught up.

Bran kept walking, “You know how it is. Sometimes Raven finds Wolf a whole herd of moose. Sometimes he’s on the wrong trail, just chasing shadows.” He tossed the snack bag into the back seat of the blue Jeep, hopped into the driver’s seat. He started the engine, the radio booming off the Turkey Hill’s wall. Ian went astern, ducked under the protruding tails of the two sea kayaks lashed on the roof racks; one deep sky blue, one in the earth tones of hand worked wood. His shorts-clad legs passed bumper stickers; Save the Bay; I love my fur wheel drive (with a picture of a sled dog team); a sticker for a pilot’s association; a dive flag. The Jeep’s door slammed shut. Across it a raven the

color of storm skies spread broad wings against a pale moon. Below, in windblown letters it said Ravin’ Maniac, beneath that, in neater type; Earth Life Foundation, Hawk Circle Farm; Educational and Research Center. Ian flumped into the passenger seat, reaching for his seatbelt as the Jeep roared off.

“Hey...” he fished for the ends, and after three failed attempts mated them. He looked over at Bran. Bran who could, and usually did, match any singer on the radio. Perfectly. A classic Jethro Tull song was blasting forth, and Bran wasn’t singing.

“What?” Ian said, his voice lost in the radio noise.

Bran glanced at him and turned his eyes back to the road. He shrugged, “Just shadows.”

“For now.” Ian said under his breath.

The Fish and Boat Commission’s ramp was quiet; a couple of trucks with boat trailers dripping puddles onto the blacktop, one beat-up Subaru with empty kayak racks. Ian slid the wooden boat off the racks, eased one edge of the cockpit over a broad shoulder and set it down carefully at the edge of the water. Across the round swell of deck forward of the cockpit was the name Artemis. He lined up the drybags with their week’s worth of survival and scientific gear by the boat, weighing each carefully in his hand. He considered the two storage compartments, fore and aft, and how to divide the load between them. His boat needed to float level, and the correct gear had to be available at the right time; one could not pop a hatch on open water to retrieve a camera, or a bag of gorp, and a drybagged tent on deck would be clumsy and a windcatcher.

At last Ian opened a hatch and placed tent and spare water and food inside, sealed it. Popped the other hatch and carefully placed two drybags stamped with the Earth Life Foundation logo inside. Another drybag, with basic camera gear, went in the Artemis’s cockpit. One last bag, a small bright green drybag with gorp and chocolate and a few other items also went into the cockpit. Lights and bilge pump and hat and dive slate for notes went under the deck bungees, along with a camera in a waterproof housing. PFD and paddle, on its leash, were tossed loosely in the‘pit, for now.

“Ready?” Bran already floated in Sky, paddle stroking the current like a bird’s wings holding steady in wind. “We got a job to do.” He adjusted a

tracking device thrust under a deck bungee. Ten yards away, ashore, a flash of blue and a loud voice announced the presence of a blue jay. Bran glanced up, then stared at it, as if listening.

“Usually you’re the one running on elvish time.” Ian said. His friend’s face was oddly quiet. Ian glanced at the branch ashore, now empty of its flash of blue. His eyes went back to Bran,“What news from the wood, Wolf-bird?”

“Lots of moose crashing around.”

“Oh yeah.” Ian said. Hunting season. Lots of guys taking their guns for walks, most with the attitude of dominating the woods, instead of being one with it. Ian lifted the Artemisinto the water, slid into the cockpit, snapped the sprayskirt around the coaming. With a nod to Bran, Wolf bowing in an invitation to play, he dug into the rolling brown water, and shot ahead of the blue boat.

Behind them, the Susquehanna rippled like a horse’s mane flying in the wind, brown and shallow, through rock gardens and riffles, around tree-studded islands, pooled into wide lakes behind dams, rolled on past farm and wood and city to the wide waters of the Chesapeake Bay, then down to the sea. North, toward the mountains of upstate Pennsylvania and New York, the river narrowed, became ever rockier, faster. Sky and Artemis were sword blade shapes, meant for the open reaches of the Bay, the sea, not for dodging around rocks, like the little whitewater boats, agile as squirrels. But whitewater boats were slow, and could not carry the gear they needed for this mission, and here the river was open enough for a long boat. These boats could knife through the fast water like birds on the wind, as long as their paddlers could avoid the

rocks hidden just below the surface. Rocks beginning to make their appearance above water all around Sky and Artemis’course.

“Hey,” Ian called back, “I think you should lead now.”

“Yeah,” Bran said, pulling alongside, “Will the people with the plastic boats please go first. So I can find the rocks before you do.”

“You know how long it took me to build this thing?”

“About as long as it took my crew to build a two-masted, hundred-foot, sharp-built schooner a couple of centuries ago.” A flash of Bran’s old privateer grin returned and he paddled ahead, pulling away from Ian and Artemis as easily as if he had an engine stashed under the deck.

Around them the worn hills of south-central Pennsylvania lay, wrinkled like a comfortable quilt, the full skirts of a mature goddess wearing burgundy and gold, and dusty autumn greens. Cormorants spread drying wings on snags. Crows called from the woods. Seagulls circled up from the bay. A pair of bald eagles, their plumage still the splotchy brown and white of youth, swooped down, feet reaching out to snag fish. Flotillas of ducks and geese found shallows to rest in. One raft of floating waterfowl seemed to Ian to be especially unwary, the two kayaks were well within their flight radius, and the birds seemed not to have even noticed them.“Hey wingnut, I think I finally got it.” Got the idea of

how to glide up to wild things who did not normally trust humans in boats. Wild things that ignored Bran, or accepted him as brother. “These guys aren’t taking off.”

“Those are decoys, Maddog.”

“Crap.” Ian said, slicing away from the plastic geese, bobbing glassy-eyed on their anchor lines.

Rocks carved by glacier and flood rose from the great river, trees clung to some, nothing bigger than a bush to others. The river wove around them, all the water from the north pressing now into narrow channels. It ran faster, ricocheting off hidden rocks and sunken trees swept down in spring floods. Water welled up in pillows, spun in slow whirlpools, ripped in the narrows. It was not impossible to paddle north against this great power, not any harder than a bird riding the wind, if you knew how to read the river. If you knew to slide your boat across the still pillows of water rather than through the ripping current. If you knew that the water on the other side of the eddyline flowed upstream. If you knew when the water was revealing what lay beneath, and when it was hiding it.

Ian followed the blue boat’s trail. He had ridden the river enough to know most of its language. But he was only human, and his knowledge of that language was elementary. It was not the instinctive empathy or agelong learned wisdom of the Firstborn Children of the world. That was Bran’s; the reading of wind and cloud, of the dance of light on the surface that meant a rock was lurking below, the feel of the water as it deflected around a drowned tree, the pattern of wave ripple that meant an island was just beyond the sea’s horizon.

Bran could do the simple ferry across this piece of channel in the dark with his eyes shut.

Ian breathed, like a wolf sighting prey. He poked the Artemis’s nose into the current, plunged his paddle in on the current side and threw every

ounce of his considerable muscle into pulling the Artemis forward, and to starboard. The boat slid to the right, nose upstream, the current ripping by on either side. She rocked like a galloping horse. Ian balanced, loose-hipped, focused on keeping her nose pointed upstream and slightly starboard. Not far enough, and he would sit here while the river ran by. Too far, and the river would haul him sideways, yank the boat from under him and send them both downriver on their faces. The Artemisslid to starboard, easing across the current. Ian grinned, let out a whoop. This was paddling. This was why he was here, tracking invisible otters, getting mosquito bit, sleeping on a quarter inch of closed cell foam. “Yeeeeah!”

Something hit his gut, as if a moose had kicked him. His stroke faltered, the kayak twisted beneath him like a spooked horse. He dug his paddle in on the starboard side and pulled. Stroke, stroke, stroke. She straightened out, nose upstream again.

Bran’s boat was coming downstream straight at him, broadside and upside down. For two strokes of the paddle he didn’t believe it. Then he thought it might be an impromptu rescue lesson for his own benefit; Raven yanking Wolf’s tail. “What the hell...” It took seconds to spot the flash of bright red that was Bran’s PFD. Ian thrust the paddle against the current and the Artemis shot north. A few strokes later Ian presented his bow to Bran. “Grab on!” Ian said.

“Never mind me, get Sky!”

“Swimmers first.”

“I’m fine! Get the bloody boat! And any gear she dropped!” Bran’s face was not the calm face he wore when he was egging Ian on to learn something. It held barely contained anger.

You did not do that on purpose...this was not a test. What did you see? What did you feel? Raven could see; not just things at the edge of the horizon, things beyond it, things unseen by Wolf. Raven had felt something, and Wolf had caught its echo.

Ian heeled the Artemis around on the current, leaning downstream to keep the river from yanking the boat out from under him. A few hard strokes and he caught up to Sky, flying on the current. He herded the blue boat, pressing his own against her side. He stuffed his paddle under a deck bungee, drifting with the current, caught Sky, heaved her over his bow, upside down, and drained most of the river out. Finally, he lashed Sky to Artemis. He inspected the gear on deck, in the cockpit; all there.

He pulled the GPS unit out from under a bungee. The acrid smell of burnt electronics met his sensitive nose.“Fried. Earla’s going to love this. Another piece of electronics to replace.”He checked the tracking unit. Fried too. The compass seemed to have also been the victim of a random electromagnetic event. Ian shook it uselessly. With some effort, he turned both kayaks around and headed back to Bran, floating downstream, wet-suited toes poking out of the water. Bran caught Sky’sproffered bow in his hands, slid across the deck as easily as a bareback rider on a pony, slipped back into the cockpit. He let it drift downstream while he finished pumping out the cockpit.

“What the hell, you ferry worse stuff than this all the time.” Ian said. “That’s like paddling a pond for you.”

Bran stayed silent, as if he was listening to something far away.

“Whatever hit you, hit you hard. Everything’s elf-toasted.”

“Damn.” Bran said, and to Ian it seemed he wasn’t talking about fried electronics.

He said no more, just pumped the last bits of river out of his cockpit, head cocked toward the far shore, as if listening.

Ian waited, holding both boats steady in the current. Bran would tell him what he knew, when he felt like it. When he could see something more than shadows.

Bran crammed the bilge pump back under the deck bungees, snapped his spray skirt back in place and retrieved his paddle from the end of its leash. Overhead a crow called out, loud and sudden, Bran’s eyes followed it, then he dug in, not the long low stroke that would last all day, a high hard stroke that would move him through the water like lightning. Like stormwind.

Crow. Another corvid, like Jay or Magpie or Raven. Ian thrust his paddle into the brown water and followed. His paddle was spinning like a wheel with his effort, but he could not draw alongside Bran. He had only enough breath for paddling, so he did not ask any random questions. They paddled north in silence, not the silence of long time friends. The silence of Wolf running hard after Raven. Raven who has seen something, but is not sure whether it’s an easy carcass, or a strong bull moose.

They knifed across the rest of the current, through the shallows on the far side. Ian saw Bran scrape over a submerged rock and ignore it. Ian swerved around it, lost a few yards, paddled harder. Rocks and earth and trees loomed. Not one of the islands inhabited by summer cabins and beer parties. The Lancaster shore. A sunlit golden wood, with quiet water rushing by. A couple of crows called from somewhere in the wood “What are they saying?” Ian called to Bran. No answer.

Inland and upstream, dark wings circled. Ian measured them with his eyes; not the broad pinions of eagles. Not the circling flight of a redtail hawk. Not the shallow V of turkey vultures. Black vultures, soaring flatwinged like big ravens on the air currents above the hills.Their scientific name, coragyps atratus, meant raven vulture.

Scavengers, homing in a kill. Maybe a deer lost by a reckless hunter. Maybe roadkill on a river road Ian could not see.

Something in his moosekicked gut said different.

Bran drove Sky hard onto a mudflat rimmed by steep earth, rocks and tree roots. He rose from the cockpit, caught the bow toggle and hauled the boat up the bank onto high ground. Ian followed.

Bran stood listening into the woods, one hand splayed against a tree trunk. His spray skirt and PFD had been thrown into his cockpit, his bright blue and gaudy green wetsuit was an angry flame of color against the goddess golds and burgundys of the woods.

“What?” Ian said softly.

“Get the Green Bag.” Bran said, with the weight of air before a storm.

Ian gave him a sharp nod, retreated silently to his boat, found the bright Green Bag in the cockpit, the survival bag. He slung it over his back,

but not before removing one object from it; a mooncircle of aluminum, the color of storm skies. It was stamped with a simple radial pattern and had a hole in the center which might have once held a knob. He trotted back to Bran, the ex-pot lid in one hand.

Bran made a Sign; silence. And another; mindlink.

They moved, like sled dogs on a team. Wolves, hunting. Two birds, wheeling on the same wind. Ian crunched lightly through fallen leaves, his

wetsuit boots making less noise than a deer hunter’s heavy boots, but more than Bran’s silent feet. The black neoprene of his wetsuit would make him no more than treeshadow if he stood still. If he misdirectedwatchers.

Bran was running ahead, in blinding colors, and weaponless.

No, he was never quite weaponless.

Up the hill dropping her feet into the river, over branch and rock, finding the deer paths through tangled brush. Raven the Seer, Wolf the Hunter. Raven finds. Wolf brings down the prey.

Split up?

No. Not yet.

They ran. Bodies flowed around tree boles, slid past twig and tangle. Feet cleared rock and fallen branch, found purchase on a single stone, a bit of root, a place less muddy. The woods was silent except for the occasional voice of the distant crows.

Then the sudden shrieking jeeaahh!of a blue jay.

At the base of a rock face, Bran stopped.

In the red and yellow leaves at his feet Ian saw blood.

Bran stood, two yards away, looking down, his face still as a deathbird mask.

Ian pounded up beside him. Sprawled at the base of the rock face was a dog, dismembered and bloody. The tortured mess had once been a big black Lab.

The aluminum disk Ian held fell. He was Wolf, as were his rescued malamutes back home, as were all canines of any form. He felt it as if it had happened to one of his own children. To him. Rage, grief, frustration, he could not name the emotion, but it poured out like a river in storm flood; in one fierce howl. When he could think again, it was with all too human hindsight; If we had been faster. If we hadn’t stopped at the store. If...if...if...

“It was only uncertain shadows, then. I was not sure...” Bran’s voice faltered, fell silent. He knelt, fingers reading leaf and blood and soil...and what lay beyond it. He looked up at the flash of blue in the tree above. His eyes came back to Ian, “It would have made no difference if I had flown from the river in raven form.”

“I didn’t say that.”

“I know. I thought it.” He let out a hiss of frustration.

“If they were still here...”Ian said, the words as quiet as a knife unsheathing. Ian felt a hard hand on his shoulder.

“They are still here.”

Ian stood, one hand clenched around the moonsilver disk, blotched with blood.

Bran’s hand moved like the twitch of flight feathers. You go that way.

Ian ran. Behind him a wind sprang up from the river, lifting leaf and bringing with it mist and river spray.

The wind swirled, departed. One set of wet suit boot tracks led up, over the hill. The others ended.

A raven, the color of storm skies lifted off from that spot, his wings whooshing noisily against the autumn air. He swept between tangled leaf and bough, easily as if he were sailing on open sea. Sun and shadow danced across his back, silver and pewter camouflage. He did not cut through the air, he did not ride the air. He was part of it, every feather an antenna, he could feel the shape of the air, how it lay cool and heavy in the shadowy hollows, how it rose from the warm breast of the earth mother. He could feel the trees, roots reaching into the dark rich earth, limbs lifting into the sky.

The sky a distant Grandmother had given him when she married one of the Elders. The sky a stormsilver raven had given him after a lifetime of studying that one bird.

Raven usually flew with joy, with abandon; tumbling and dancing on the wind.

He flew hard and straight as an arrow. And with all its deadly intent.

Ahead, something interrupted the pattern of wind and squirrel rustle and reaching tree. The raven banked hard aport, lifted above the trees for a moment. Dived back under the canopy. There. A lone figure, small, scrambling up through the cracks of glacier tumbled rock.

Raven flared, landed on a rock ahead of his quarry. He watched it climb toward him, oblivious of watching eyes, oblivious of the sun at its back, the wind in its hair, of the distant rush of the river.

It would be easy to startle it. Send it over one of those rocks.

Ian hammered through the woods with none of the grace of the Firstborn. He could run quiet; he could weave around tree bole and branch, his feet could find purchase on loose log or shifting rock or mossy slope. He could lighten them, not as much as Bran, but he could run lighter than most Men. All of that was forgotten in his anger.

Not anger. Fury, rage, wrath. What kind of....there was no curse in any language he knew that would describe such monstrosity...would do that

to a dog?

What else was such evil capable of?

Brush and branch were swept aside or crushed. Deer turned, flagged their white alarm signals and fled.

Wolf was not hunting them. He was hunting something he couldn’t see. His wrath flared, he pushed it down, a hot fire banked in his center. Think. Think. Where is he? Bran...Bran? Where did he go?

The answer came, a thin trail of thought, a picture, as if from a great height, a lone figure climbing through the trees.

Ian shifted to starboard, ran harder.

He came out on the ridgeline, breathing hard. He scanned the woods with eyes and ears. There, a disturbance in the quiet web of life. A squirrel running, two birds taking off.

He ran, quieter now, keeping to the treeshadow. Just below the ridgeline where he could not be seen against the sky, neoprene clad feet hitting rock and bare leafless soil, quiet as the padded feet of Wolf. He halted, saw movement below him. The wrath flared again, he banked it down again, he needed to think. Think! He studied the dark figure below him. Not a random hunter.

Its aura didn’t glow, it sucked light in, black and twisted like burned out forest.

Ian’s green eyes blazed with leaflight, he raised his hand, still clenched around the moonsilver disk. His grip loosened, it dangled in his hand

like a live thing. His hand swept out in a great bowcurve of motion.

The moon disk flew, swooping around tree and branch like a bird. It spun, dropped and hit Wolf’s prey square in the back of the head.

Wind swirled around the rocks, bringing with it leaf litter and stray moss and water from air and earth.

One hundred and sixty pounds of water, more or less. It coalesced into a pillar, shifted its shape and a man stood there, in a short wetsuit of mountain sky blue and leaflight green. He hopped from the rock without a sound, caught the throat of the small figure frozen in disbelief before him and slammed it against a boulder.

Bran took only passing note of the camo pants and dirty flannel shirt. Clothes were like the surface of the water, they told you some, they hid more. He looked past that, to the creature’s aura. It writhed, twisted with stains and scars and dark light.

Not wholly dark.

Bran’s hard blue eyes met the eyes of his prey and he realized he was holding the throat of a thirteen year old boy. The boy was trying to sob through the strangle hold on his throat, there was no fight in him, he had gone limp as a dead squirrel.

Bran dropped him on a rock, seat first. The boy huddled there, sobbing. For a moment it sounded as if he might be trying to force words out between the sobs, but Bran wasn’t sure.

He stared at the boy, trying to make sense of it, but this sort of thing made no more sense to him now than it had five centuries ago, or ten. He

crouched before the boy, took his face in a grip as hard as Raven’s swordblade beak. “Look at me.” he said levelly.

The boy’s eyes were the color of forest soil. The dark, rich soil from which everything grew. Bran studied them, looked beyond them. Saw.

“You thought to summon Power. Well, you have summoned something. Me.”

The boy had already made himself as small and insignificant as possible. Impossibly, he tried to shrink even farther into the rock he was huddled on. He tried to pry his eyes from Bran’s and failed. He did not know what it was he had summoned, only that it was older than dirt and stronger than he was. There were words for it in his tongue, but, for this boy they would only conjure silly butterfly images; not longbows and silent feet, not broad dark wings carrying the light into the sky.

Bran’s eyes swept over the muddy sneakers, the bloodied clothes. Why? Why do humans want power? Dominion. Why do you not feel the pain of others? Why did you do... Bran looked into the boy’s heart again and saw. Saw things no child should see. Things no child should

experience.

“You want Power over them, over the ones who have hurt you. You can’t summon it with dark rituals, even if you knew how to do them properly. You have to find it. Here.”

Bran tapped the boy’s chest with a swordblade finger.

“Go. There is one you can talk to. One who will help you. You know who I mean.”

A small voice choked its way through the sobs, “But...”

“You have a choice. You always have a choice. You do not have to follow your stepfather’s path. If you do, this is what’s on it.” He looked into the boy’s eyes, beyond them, and the boy saw...

Darkness and fire. Sword and bloodied limb. Krahe, deathbird. Battle Crow. Morrigan’s ravens picking out the eyes of the dead.

The boy sat, deathly still, wide-eyed in fear.

“Go.” Bran said softly.

The boy stood, shakily.

Bran reached both hands behind his own neck and removed something. He held it out to the boy.

The boy stood, too frightened to move.

Bran slid the necklace around the boy’s neck; a string, a few river shells, a small silver feather shed from his own wing coverts. “This will

protect you for now. His glance will slide off you. He’ll forget you’re there. You know what else to do.”

Above them crows called in the trees.

Bran half smiled, “We’ll be watching.”

Ian thundered down the slope, stealth forgotten. His quarry was down.

Mostly. It floundered on hands and knees, clutched at a sapling, drew itself up; a beer-bellied figure in black, cocky fire in its eye, challenging

sneer on its pale, sunburned face.

Black. Black pants, black jacket, black aura. And behind the beer belly was height and muscle.

Ian collided with him at full tilt, Wolf grabbing Moose by the nose and hauling him down.

Moose did not go down easily. He lashed out with a leg, caught Ian in the ribs.

Ian rolled with it, came up running, despite the pain. A sweep of his own leg and his prey foundered, went down.

One gasping breath, two. The big man rolled to his feet, charging Ian like an angry bear.

Ian slid out of the way, like a raven banking in flight. One hand slipped out, knife-edged.

Moose’s throat collided with it at full speed. His legs and ass and beer belly went airborne, his head hung in mid-air for a heartbeat, then the whole mess crashed into the leaf litter. Ian leapt on him, one hand raised in a strike he had practiced endlessly. Practiced to perfection. Practiced with the knowledge that he would never use it. It would not disable an opponent. It would kill an enemy. Kill him in less than a heartbeat.

He did not want to kill this enemy. He wanted to annihilate him. To crush every bone, every muscle, every blood vessel. To scatter it all to the four winds. To obliterate every cell, every molecule, every memory of his existence.

There was the harsh whistle of wind through flight feathers and something hit Ian in the back of the head.

A single word, exploded in his head.

NO!

Ian struck. The perfect palm strike. The one that could break multiple boards. Concrete block. The one that amazed the third graders last

year.

Ian’s hand passed through the edge of his prey’s short hair. A rock by its ear danced with faint green light and broke with a crack like

thunder.

Wind tore around the combatants, stinging dirt and leaf litter into their eyes.

Ian crouched on his prey’s chest, trembling with rage.

Bran knelt before him, “Ian,” he said so softly it might have been wind.

Ian raised his hand. Clenched it. His prey threw him off, began to scramble away.

Bran moved, easy as Raven tumbling on the wind, and stood in his path, hands raised like a heron waiting to strike. “Stay.” Bran said, meeting the prey’s eyes.

The prey wavered, head low, like a moose testing the power of a determined wolf.

Bran took a step forward.

Moose sat, eyes fixed on Raven’s face.

Ian let out a howl of rage, frustration. Pounded the trunk of a nearby tree. Then he stood, leaning against that tree for a full minute, as if it were

his mother. When he finally looked up Bran was crouching where he had been, their quarry sprawled on its ample ass a few feet away, its face cold and unreadable.

“What happened to the others?” Ian said, and his voice was almost calm.

“I let him go.” Bran said quietly.

Ian let out a dry heh. “Like Ahhnold, in, what was that movie...you just drop him off a cliff?”

“Almost.” Bran looked up, sky eyes met earth. “He was maybe thirteen. His stepfather likes to beat him up for fun. Among other things.”

Ian saw what Bran had seen and looked quickly away. Been there, done that, got the battle scars.

“He has a teacher. One he can trust.”Bran said quietly as a feather falling.

Ian’s eyes went to Bran’s neck, exposed by a partly unzipped wetsuit. “You gave him the necklace.”

“He needed it. I can make more.”Bran returned to studying the man before them.

He might have been eighteen, or twenty-something. Wearing the kind of black pants worn for paintball. A black leather jacket. A lot of gaudy necklaces over the black t-shirt beneath; some with symbols Ian recognized, symbols that belonged to legitimate spiritual paths, paths this one was corrupting. “There was just that one?”

“Yeah.”

“Now what? We call the SPCA? The cops?” Anger crept back into Ian’s voice, “You know how great human laws are about stuff like animal torture. A slap on the wrist, a little community service, maybe a fine; enough to take his beer money away for a week.” Ian paced, four steps one way, four steps back, twig and branch crunched under his feet, unnoticed. “What about next time? You know next time it’ll be somebody’s grandmother, pulling out in front of him on the freeway. His girlfriend looking too long at the guy behind the counter. Somebody’s kid.”

Bran crouched, studying their prey.

The prey seemed to be studying him back.

“I really wanted to....” Ian said.

“You were going to kill him.” Bran said flatly.

Ian stopped pacing, his eyes fixed on Bran.

“You know the Rule of Three.”

Whatever you do comes back to you in threes. “I know. I know.” Ian breathed out the words and some of his rage went with it, he collapsed on the damp leafy earth next to Bran. One hand went to Bran’s shoulder. “Thanks. For hitting the human in its concrete lined head.”

Bran gave Ian’s head a gentle push. He almost smiled.

“I’m glad you found the kid.” Ian said. What would I have done? He didn’t want to think about that too closely.

“Maybe, if I had been a little later here, you would only have broken a rock.”

“Maybe.” More of Ian’s rage poured away. His body slumped, head on knees. He contemplated the colors of the earth mother beneath his

feet.

“What about this one.” Bran said, half to Ian, half to himself.

Ian looked up, “What do you mean?’” Show him the truth. Show him who you are. Show him the kind of power that’s out there. Power that’ll kick his ass into the next reincarnation.

He knows what I am. He’s fascinated, but not all that impressed. And he is not powerless. “His aura crawls with black light.” Bran said aloud,

“He feeds on pain, on death. What should I do? Shrivel his soul? Burn his mind? Drain the life from his body so that he spends all his days contemplating his own pain?” He shot a knife-edged glance at the prisoner.

The man stared back, eyes pale and cold as ice.

Ian collapsed back on his knees,“Rule of Three.” You would only burn yourself, Ravenkin. He watched the path of a bug wandering across the

leaves. He studied the dance of greens and browns in one fallen leaf. At last he looked up, “What about the Grandmothers?”

“How do you propose to get him back to Hawk Circle? With two kayaks. And, in our wisdom, we entrusted me with the com.

“Fried, with the rest of the gear. But...” Ian dug into the Green Bag, produced a cell phone, held it up, half smiling, “...didn’t trust you with all

the electronics and communications gear.” He beeped out a merry little tune on it, on that seemed eerily out of place in this bright wood full of death. His smile faded. “Bloody hell.” He said.

Bran cocked a questioning eyebrow.

“No phone zone.” Ian stuffed it back in the bag. “I’ll just hike out, get a phone at a fast food joint or something, or find a spot the cell actually

works. I’ll call Tas to come with the van.”

Bran shook his head, “We cannot simply walk him out, swaddled in duct tape. And Tas can’t teleport far enough to come to us.” He was silent for two breaths, “And she would not hesitate to kill him.” He contemplated the shape of the shadows against the tree boles, the pattern of leaflight on the red and gold tapestry of the forest floor. Do not leave me alone with this one.

Why? You know the rule of three better than I.

I said he was not without power. Raven needs Wolf to keep the bears at bay. And I have a feeling...

A feeling? Chasing shadows again?

We should wait here, for awhile. "Besides," Bran said out loud, "the Grandmothers would say this is our issue to solve."

Silence. Maybe a few breaths. Maybe a few minutes. Maybe longer. Awhile could be minutes, or weeks, or years if you were talking to an Elf.

“It’s kind of chilly.” Ian said at last. “I think I’ll make a fire.” He glanced at Bran, clad in the same kind of light wetsuit he was.

“Good idea.”

Ian stood, the shadows had crept farther along the forest floor. The nameless man still sat, hunched like a vast and unsavory toad, under Bran’s watchful gaze.

Ian stretched, flinched at the pain in his ribs. Opened and closed his hand. That hurt too. He could heal it. He could draw on the warm life energy of tree and rock and earth itself and make the hurt go away.

In his mind he saw the poster in the convenience store with its childish crayon scrawl, a smiling toddler hugging a big black protector. There were some hurts here he could not make go away. He walked into the woods, looking for downed branches. When he’d found an armfull he brought them back, ignoring the pain in his ribs, in his hand. He scraped away leaf and twig and all else that would burn. A circle of clean earth in the woods, golden with afternoon sun and unfallen leaf. He knelt and arranged the branches and drew the firestarter from his pack.

In a minute, smoke rose like prayer, like departing spirits, through the canopy of the golden wood.

Bran stayed silent. Bran who always sang, even if there was nothing to sing about.

Their prisoner stayed silent too, icy eyes shifting from one to the other. He tried to get up once. Bran rose, flowed up from the forest floor, his

eyes fixed on the man, one hand folded like a raven’s beak, waiting to strike.

The man sat down, watching them. Waiting.

In the bottom of Ian’s pack was a small smudge stick, white sage tied in a bundle. He pulled it out, looked at it.

“Save some.” Bran suggested.

Ian put half on the fire, its pungent smoke rose with the smoke from the damp wood. Prayers, lifting to the sky gods.

If any were there to hear. Some of it drifted toward their prisoner. His icy glare shifted to annoyance, then a shadow of apprehension. He shrank away from the smoke.

The purifying smoke which drove out the dark.

Ian fidgeted. Bran perched on a rock, rising out of the river of leaves, coiled like a watching cat. Ian had seen him sit like that for an entire day.

Longer. He stretched, shifted. Rearranged himself again. The E.L.F. would contact them, somehow. Somewhen. Track them down with a message from the magazine who had sponsored the otter project, they would wonder how things were going.

Wonderful. The Good Guys are just sitting here waiting for the Dark Lord of the Bling to die of natural causes.

Ian turned the moondisk over in his hands. Magic he had been gifted with. Magic a mere human could wield. There was greater magic out there. He had seen it. He lived with it.

Where was magic that would bring justice to a dog?

Frustration and rage rose like a dragon unleashed. Ian flung the disk, it sliced through the smoke from tree branch and sage and vanished into the trees. He collapsed, his head on his knees, face hidden.

The autumn woods, already quiet, fell silent, as if it was holding its breath.

Something crunched lightly, a footstep on twig and dry leaf.

Ian looked up.

A dog stood at the edge of the woods, the moondisk in its mouth like a frisbee. Ian blinked, the apparition didn’t waver.

On the other side of the fire, Bran stood, an expression of wonder on his face.

It was not just any dog. It was the color of the woods, greys and browns and yellows mingled in its grizzled coat. It looked a lot like an Irish

Wolfhound.

One somebody had crossed with a horse. Its jaws, holding Ian’s moondisk, were easily level with Bran’s chest. Leaves rustled lightly behind Ian, and to either side. Three more of the immense hounds walked out of the woods.

“Braaaan...” Ian said softly. He rose slowly, smoothly. Reached carefully into the Green Bag for a second disk. The dogs didn’t move, though their eyes followed him.

“Drop that.” Bran said, motioning to the Bag. And he closed his mouth on whatever else he was going to say because at that moment the hounds’ handler walked out of the woods too.

A Pennsylvania bowhunter, in Mossy Oak Break Up camo, hands, face, everything obscured by photorealistic bark, leaf and limb.

”Wha...?” Ian whispered. Then he saw the bow, poking out from behind the hunter’s shoulder, not the usual wires and pulleys of a compound bow. This was a traditional longbow.

A really big one.

The hounds stood, one at each compass point, eyes on their master.

A gloved hand reached, withdrew the camo hood.

Mistress. A middle aged woman stood there. Her face had the clean hard lines of deer antler and wolf tooth and falcon talon. Her eyes swept the circle around the fire, a hunter assessing a trail, a sign, the taste of the morning air. She turned her treeshadow eyes to Bran, he smiled and bowed, as if to a queen.

As if to a goddess.

She nodded in return, her eyes moving to Ian.

“My lady.” Ian stumbled over the words, and bowed, like Bran. What lady, he had no idea. But he was fairly sure, if the Game Commission stopped and asked for her hunting license, she would not produce one.

She signaled to the hound holding the moondisk, he came to her, placed it in her hand. She turned it over, studying it, ran a finger around its edge. She stepped up to Ian, her feet utterly silent. She looked up at him, “This is yours.”

“Yes...my Lady,” he managed to say.

She glanced at the prisoner. Back to Ian.

“I...I’m sorry, I should not have thrown it away like that.” Ian said.

“It was a prayer.” She said, “A rather forceful one.” She held it out to him, and he took it. “Moon magic. Not many men can wield that.”

“He’s an unusual Man.” Bran said.

She held it out to him again, her voice the voice of a commander, “You have always used this well. Continue to do so.”

Ian took it from her hand, brushing her fingers for an instant. It felt like warm earth, like a mother’s touch. Like the edge of an arrowhead. His disk shimmered with new light. He looked at the forest floor, feeling suddenly very stupid, very small. Very insignificant..

She lifted his chin, looked into his green leaf eyes, smiled like sunrise. Her eyebrows quirked in a questionmark,“I don’t suppose you have any

chocolate?”

Ian stared, his brain not quite ready to process chocolate and...whoever this was...in the same sentence.“Ss...sure.” He knelt and fumbled in the Green Bag, found Bran’s chocolate bars and held them out to her. All four of them.

She took the chocolate with the grace of a queen and the hunger of a wolf, hunting. She peeled one bar as if she were skinning a deer, carefully sticking the paper into a pocket of her Mossy Oaks. She turned toward Bran and the prisoner, chewing thoughtfully.

Ian could see the whole bow now, a long mooncurve dancing with faint silver light. The arrows in the quiver were fletched with velvet edged feathers in camoflage colors; gold and brown, like the light on the forest floor. Familiar feathers.

Great Horned Owl. The Tiger of the Air. The stealth hunter. Ian felt his neck hairs curl, the way they had the first time he’d held a GHO on one

heavily gloved fist.

“Let him go.” The Huntress was telling Bran.

What?

The man, unimpressed by the small woman before him scrambled clumsily to his feet. He stared around the circle; Ian, Bran, one small huntress and four huge hounds. His lip lifted in something that would never have passed for a smile. His eyes traveled over the huntress again.

“Run.” The Huntress said.

He stared at her as if she’d spoken Greek. “Whaddaya gonna do, shoot me? There’s laws...”

The bow was in her hand, an arrow drawn. Ian had not seen how it got there.

“I answer to a greater law than the local, temporal laws of humans,” she said. The bow creaked slightly, the arrow dropped, leveled at a target well below his heart. Her eyes blazed golden, like the owl’s.

His widened in disbelief.

The bow creaked a bit more.

Disbelief changed to fear. He took a step back. Two. His foot found a rock, shifted.

Melted. Shimmered in the late afternoon sun and treeshadow. A hoof scrambled for footing among the rocks and tree roots. One hoof, then another. The change swept up his couch-soft body, legs and arms stretched, thin and strong as the mooncurve of bow in the woman’s hands. His squatty toad shape shifted, flattened, muscles bulged, neck stretched.

A magnificent rack of eighteen points sprouted from his forehead. Legs clad in hollow hair the color of treebark scrambled desperately, as his brain adjusted from two wheel drive to four.

The big buck crashed into a tree, floundered back up, staggered off, crashing and falling and scrambling to his hoofed feet again.

The huntress loosed her arrow. It winged straight and true, gouged a long red streak in the buck’s flank and stuck in a tree.

“You missed?” The words fell out of Ian’s mouth before he could stop them.

The Huntress turned to him, smiled like a wolf. “I never miss. That was just an incentive to keep running.” Her moonlit eyes turned back to the woods following the distant crashing of buck through brush, the flight of disturbed birds. The distant shriek of a jay. It sounded like laughter.

She shook her head. “At that rate, he’ll break a leg before one of the local hunters finds him. Ah well. They’ve mostly forgotten what I taught them long ago. They need tree stands and SUVs and...” she made a face of distaste, “...machines with pulleys and wires to propell their arrows, arrows no longer made of the gifts of the forest; wood and feather.” She sighed, signaled to her hounds; as one, they leapt forth on the buck’s trail. “Maybe one of them needs help filling his freezer. Or hers.”She smiled like a rising moon at Ian and Bran, turned and vanished soundlessly into the woods.

Raven and Wolf stood, watching the empty woods in silence, mouths slightly ajar.

At last Ian said, “Who was that...”

“...masked woman.” Bran finished. He stalked to the tree that had stopped her shot, removed the arrow. He held it up, peering over the razor sharp head at Ian. “I don’t know, but she left behind this silver arrow...”

Ian shot him a swift look, birdbrain.

“Which of her thousand names do you want?” Bran twirled the arrow between two fingers, spun it into the air, caught it again. He peered down its perfectly straight length. “Ray of the Sun,” he said, mostly to himself.

“Bow of the Moon.” Ian said. His eyes registered enlightenment, “Huntress. Artemis. She turned a guy into a stag, for spying on her, bathing.”

“Oh.” Bran shrugged, “I never remember. It’s all Greek to me.”

“She let his own hounds devour him.”Ian stared into the woods, their glowing golds deepening, with the falling sun, into the colors of blood.

Bran moved to the fire, kicked it out, cradling the arrow in one hand. “By the way, did you have to give her all four chocolate bars?”

“That,” Bran said redundantly, “is a three hundred dollar kayak paddle.”

Ian thrust it into the rocky unyielding earth of the hillside and dug deeper. “I know. You know. You got it for me.” He dug again, making the hole

just a shade deeper. Behind him, the tops of the trees glowed with gold so bright it hurt to look at it. The feet of the hills below him were in deep shadow. He had been digging for some time, he didn’t know how long, but the hard bones of these hills lay close to the surface, and space unoccupied by rock was occupied by tree roots, clinging to a near vertical landscape.

“Let me.” Bran said for the umpteenth time, holding out a hand.

Ian kept digging.

“It’s not like D&D. Elves don’t carry around Raise Dead scrolls in our back pockets.”

“I know.”

“As for goddesses...” Bran shrugged.“You’d think after a few millennia I’d understand women or something.”

“I know.”

Bran held out a hand, “Give me the paddle. You should work on your hand before..”

“If I don’t do this, I will...” his jaws closed on the rest of the sentence. He clenched them shut, the paddle bounced off a rock, twanging like a

bow. He jammed it back into the hole and the thin, flexible blade shattered. Without missing a beat, he spun it around and began using the other end.

“Aaah. Human males. After a few millennia I don’t understand them either.” Bran said under his breath. He found the Green Bag, where Ian had laid it. He poked inside until he found the moondisk. He carried it to the shallow hole. On the other side the arrow already stood, silver head in the soil, owl feathers skyward. Owl; night moon bird, guardian of the gates to the spirit world.

Ian looked up from the dark earth, saw his disk in Bran’s hands, “Raven is Sun. Sky. Not Moon.”

Bran set it down quickly, on the side of the hole opposite the arrow. He sat back, hands well away from the disk. “I’m not using it. I can’t. But I think our Lady may have left a trace of her own power on it. And her power is Earth. And Moon. Like yours.” He stared into the shallow hole. Too shallow for so large a dog. Womb...tomb...womb of the earth. New moon, full moon, new moon again; Maiden, Mother, Taker of Life. The wheel, hoop, cycle, circle of life...

“If you start singing Elton John songs, I will have to hit you.” Ian said.

“Wouldn’t think of it. That one always makes you cry anyway.”

Ian buried his face under his hair and dug.

Bran stared at the dark space. Earth, from which everything sprang, where everything returned. He started singing, soft, like nightwind. A song that was old when these worn, rounded mountains were young and tall and sharp edged.

Beneath the thrusts of the paddle, the roots shifted. Rocks sank away. The soft earth yielded a space to Wolf for one of his own.

Ian placed the last bit of earth, a scoop of soil in his moondisk. Bran laid a rock, then another. Branches of evergreen. A few young plants who would grow over this mound, cycling death back into life. Below them, a small fire glowed. Bran lit the last of the sage, held it up in the dark, a single glowing ember. They sat in the dark forest, side by side, the rock face and the hill and the mound behind them. The round, waning moon showed her face through the trees over the river below.

The song Bran had been singing shifted. It made Ian’s heart ache for...something, something far away. Something he could not see with human eyes, could not reach with human strength. He lifted his head to the moon and howled; a long sorrowful song learned from his Malamutes, and from rescued wolves and hybrids at Hawk Circle. Wolves bought to enhance male egos by association; males who learned that wolves were not meant for leashes and living rooms. Wolves who would never be able to run miles under the moon. Bran’s song changed again, weaving through and around Ian’s wolfsong, two wolves singing in ten part harmony.

Something moved at the edge of the dark. Ian blinked, thinking he had seen only shadow and firelight. It moved again. A raccoon maybe.

Too big. Bear? No, not here.

Bran’s song faltered, faded into firecrackle. He peered into the dark.

Far away, so far it might have been coming from a land that only existed in Ian’s imagination, came a faint howl.“Something’s out there.” he said. Stray dog? Wandering coyote? His human eyes, keener in the dark than those of the sun-loving Firstborn, tried to decipher what he might have seen. It danced away from his night-eyes, just a shadow his mind couldn’t catch.

“It’s OK.” Bran said.

It took a moment for Ian to realize Bran wasn’t talking to him.

The shadow moved again. A definite movement this time, not just a flicker at the edge of sight. A dog walked out of the woods. Not the hounds of the Goddess. A big black Lab.

Ian’s breath caught. Time slowed, the fire seemed to pour into the air like liquid lava in slow motion. She didn’t. She did! She brought him

back. She who can take life, or give it.

The dog stepped forward past the fire and Ian could see the fire through him. The fire leapt, crackled on the other side of the shadowy form, and Ian was face to muzzle with a ghost.“What?” he said.

“He heard our song. He’s lost.” Bran said quietly, and held out a hand. The shadow dog hesitated, then nuzzled into it. “Can’t find his way home. Can’t find his pack.” He stood. “Well, then. I guess Raven will have to lead him home.” He turned to the dog, “Hey Buddy, you remember? Remember long ago, when the pack lifted its eyes to the sky and watched where the ravens went. Followed them to a fresh carcass, or good hunting.”

Ian saw the shadow jaws open in a grin, snap in a happy bark. He thought he heard a faint echo of that bark.

“Good.” Bran said. “Follow me. Come on!”

Wind swirled, nearly dousing the small fire. Startled, Buddy scuttled toward Ian, and stuck the memory of a cold nose in Ian’s hand. Ian smiled and ran a hand over the shadow of satin skin, hard muscle, great warm heart. “It’s OK.” he said, “He does that all the time.”

Raven perched on a snag, just beyond the glowing remains of the fire.

“Go on.” Ian said, giving Buddy a shove toward Raven. “The rest of your pack is waiting. Good hunting.”

It was harder than finding a dismembered and tortured dog in the woods. Harder than deflecting his own killing strike into a rock.

Much, much harder than paddling back home on Bran’s cheesy spare paddle.

Standing on the square of concrete before the hunter green door, flanked by fake birdboxes twined with grapevine and tiny white lights. Holding the collar, cleansed by soap and sage. Holding it out to the woman, her husband like a bear roused from hibernation, the two small girls staring up with wide eyes.

Ian spared them the details, except how they had buried Buddy with honors. Bran stayed mostly silent, fixing his mountain sky gaze on the woman’s nose, on the man’s beard. On the photos in the hallway; all with a large black guardian in the midst.

They thanked Ian, and Bran, and invited them in. They politely declined, suggesting a visit to Hawk Circle sometime. Educational, for the kids, you know. A few more polite small words and they turned to go.

The smallest girl looked up at Bran and smiled. She didn’t really understand what had happened. She might figure it out in weeks to come when Buddy never returned. Probably she was just too young to really understand.

“Birdie,” she said, quite clearly, meeting Bran’s eyes square on.

The bare trees made the distant hills look like wolf fur. At Hawk Circle, heaters went on in stock tanks for horses and zebras and endangered antelope, and in the bowls for the rescued wolf pack, for the recuperating raptors and resident ravens. The trails around the farm were alive with the jingle of dogtags, the whisper of running feet, and the quiet sound of wheels over stone and dirt, as the Mushing Club began to train its dog teams with rig and bike and scooter. A picture appeared in the paper of a proud hunter, a young girl, who had bagged her first buck; an impressive eighteen pointer. It had taken three shots and a lot of tracking, but she had brought him down.

Ian sat in the Hawk Circle library, mostly ignoring the noise of the school group being led on a tour of the E.L.F.’s educational facilities. He

frowned at the notes, still only halfway down page one. Somewhere behind him, chaos erupted.

“Young man!” The voice was well above the usual library decibel level.

Ian looked up to see a dog, scrabbling in panic on the hardwood floor, trying to escape the attentions of the volunteer librarian. She pointed at the young man in question, and at the doors, “Despite the fact that this is an environmental education center, that needs to be in the environment out there!” That was a scrawny yellow Lab, limping slightly on one forefoot. She dodged through the pack of fourth graders, scattering some, attracting others like magnets. Also dodging through the fourth graders was a teenaged boy in battered jeans, clutching a length of twine. Some of it was still around the dog’s neck.

“Sorry!” he yelled to the librarian,“She just got scared I guess.” The boy scrambled after her, past the Utahraptor, under the outstretched wings of the snowy owl. He caught up to her in front of the raven display. She sat, staring up at the stuffed birds in the case, as if expecting them to tell her something.

The boy slowed, halted, staring at the ravens too. Then he held out a hand, caught the bit of twine around the dog’s neck. She stood, nervously watching the horde of fourth graders circling her.

Ian made his way through them, held out a hand to the dog. She sniffed it, smiled up at him. “Stay here,” he told the boy, “I’ll get a better leash.” He made his way back through the crowd, teachers trying to create order out of the elemental chaos of fourth graders. He found the emergency leash in the Jeep, the one for strays who needed rescue, and returned with it. “Yours?” he asked the boy, kneeling by the dog to ease the leash over her head.

“No. I found her. We can’t have a dog.” He looked like he might say more, but closed his mouth on it.

Ian gave him a sympathetic smile.“Too bad.” He waited for the boy to say more.

“We’re living in a shelter,” he said at last.

“Oh.” Ian’s face showed sympathy.

“There were some kids throwing stuff at her. I scared ‘em off.”

“Damn.” Ian said to himself, he looked up at the boy, “I mean, good you rescued her. I don’t get why people do...” he remembered he was talking to a thirteen year old and rethought his choice of words, “...crap like that.”

The boy looked at the floor, looked like he wanted to disappear into it.

“Why come here?”

“I followed the ravens,” the boy mumbled.

“What?”

“The...the signs...for your airstrip. With the big silver raven on them. Couldn’t find the road for that.”He mumbled at the floor again.

“What?” Ian said gently.

“There’s this Jeep out front with the same bird on it, so I told Mom to stop here.” He made a face as if he expected Ian to think that was too weird for words.

“That’s my buddy’s, he’s on a flight so I borrowed...why raven?”

The boy stared at the floor some more, as if he couldn’t put the pictures in his head into words. He glanced up at the ravens in the display case, his eyes a mix of wonder and something else. Fear maybe, or awe. At last he said, “I seen one in the woods once.” The rest of his words tumbled out as if he was afraid Ian would stop listening. “Can you take her? I mean, the rescues got so many already, they have to kill some.”

“We can find somebody...” Ian said, his mind still on ravens. His eyes caught on something at the boy’s throat, a glint of seashell and twine.

And one silver feather.

No...no way... He narrowed his eyes, seeing the way Bran and others had taught him. The boy’s aura had stains, scars, as if he’d seen way too much for a thirteen year old. But there was brightness there too, as if a blackened forest was slowly growing out green again. “Come on.” Ian led the way back to the librarian’s desk. She glared up at both of them. “We’re leaving!” Ian assured her. He grabbed a couple of the address cards on the desk, a pen, “Here,” he thrust the pen and two cards at the boy, “Write down your name and address.”

“I don’t have an address.”

“Well, wherever you’re staying. How did you get here?”

“Mom got the car,” he said, scribbling quickly, “And a PFA. She’s workin’ on the divorce.” He handed Ian the paper.

“Good." He meant all of it. Especially the car. " You have a way to get back here then.”

The boy stared at Ian as if he had just handed him a new X-box.

“Hawk Circle’s a research facility, a rescue. A sanctuary.” For anybody who’s lost their pack. “It’s an educational center too. We got lots

of info on ravens. There’s a bunch living in the woods on the north side of Hawk Circle. There’s some people studying them, we could take you up there. And,” Ian paused, studying the boy’s face,“we’ve seen this dark silver one...at times.”

The boy looked like a kid who’d just seen a ghost and isn’t sure whether to run screaming into the night or stop and take a picture.

Ian gave him a reassuring smile.“That’s where we got the logo for the airstrip. My buddy’s a pilot. Among other things.”

“Cool,” the boy said in a voice the size of a nestling’s.

Ian patted the head of the scrawny Lab, saw the boy’s face droop minutely. “I don’t know where she’ll end up. I mean, we’ll find her a good home...somewhere.”

The boy nodded.

Ian considered the boy’s drooping face, the toe tracing the shape of the worn woodgrain. “Ah. You know....the mushers are training now that it’s cold enough, maybe you want to come out and learn to drive sled dogs?”

“You’re kidding. This ain’t Alaska.”

“No, really. We got people who train for races, for fun. Alaskan huskies, Siberians, Malamutes. I got a couple of those. Not fast, but big and strong. Couple of girls ski-joring with German Shorthairs, they’re real fast. One guy has a team of Dalmations.”

“How they train with no snow?”

“Bikes, rigs, ATVs.”

“Cool,” the boy said, a bit louder than before.

“Well?”

“Yeah. Ok. Sure.” And his face broke into a real smile.

The square of concrete before the hunter green door, flanked by fake birdboxes twined with grapevine and tiny white lights had an addition to its quiet development clutter. A yellow Lab, scrawny, with no collar or tags. The woman opened the door, “Who left you here?”

Her husband grumbled behind her like a bear roused from hibernation, “Just what we need.”

The two small girls stared past him up with wide eyes, the smallest bounced past both parents like a puppy let off a leash. She threw her arms

around the scraggly Lab and giggled.

“She hasn’t done that for awhile,”the woman said to the man.

He sighed, stepped out of the way, leaving a path into the living room, “Guess we can use up that bag of dog food now.”

“Where did you come from?” the older girl said, kneeling before the dog. She got a long pink kiss in return.

“Birdie sent her.” The little girl said clearly.

From the trees came the distinct graaack of a raven.