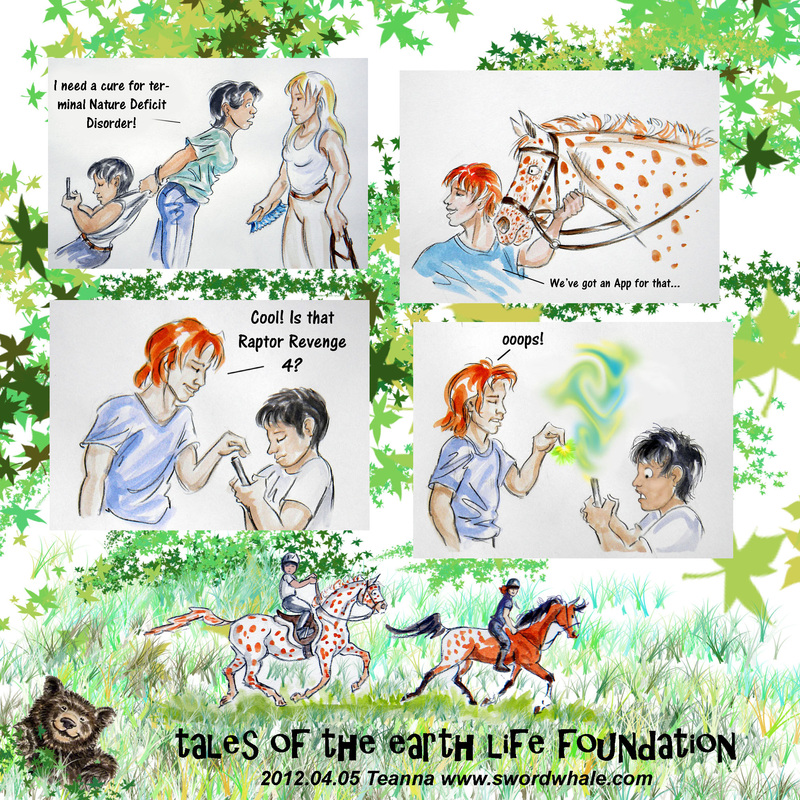

Last Child in the Woods

&

Nature Deficit Disorder: working toward a cure...

A few years ago, at Nixon Park, I noticed a book one of the naturalists was reading: Last Child in the Woods, by Richard Louv. It begins with a quote by an eight year old boy; "I like to play inside because that's where all the electrical outlets are."

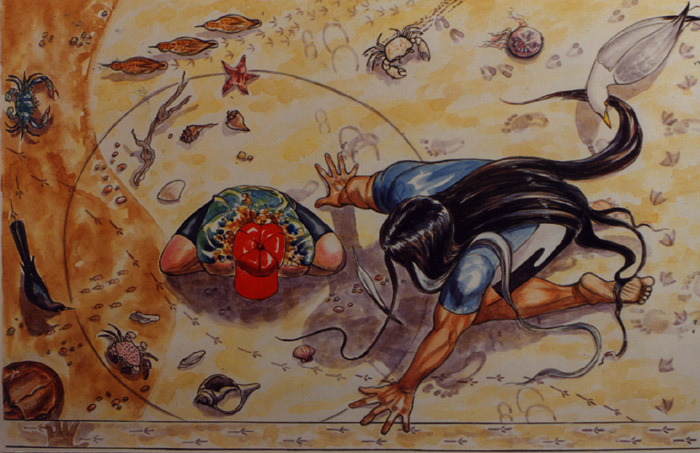

I grew up on ponies, horses, or pretending I was one, or reading about them. There was snow in the winter, which could be shaped into fantastic playmates, or tunneled into, or slid down. It melted in spring into a vernal swamp in the lower pasture, in which Barbie and friends had adventures long before we'd ever heard of Crocodile Hunter. There was a woods behind our property, not quite Pooh's Hundred Acre Wood, but big enough for hawks, mysteries, forts and explorations. When I asked my dad what he did as a kid, he said "ran around in the woods..."

I read horse stories (to the irritation of my teachers who demanded I read something else... so I read the Jungle Book by Kipling). Or sometimes a wilderness tale (those were generally unfortunately aimed at boys) like Yellow Eyes (about a cougar) or Call of the Wild. I also liked faerie tales, but those were set in a time and place immersed in nature. The most famous modern faerie tale, Lord of the Rings by JRR Tolkien, is rooted deep in the natural world, its oldest inhabitants, the Elves, hear the stones speak, talk to trees, and ride horses without saddle or rein, so close are they wired to Nature.

Richard Louv notes this generations' Nature Deficit disorder, offers up scientific evidence for why this may spell the End of the World, and what to do about it. Kick your kid outside, like my Dad's parents did: "go play outside." Unstructured play time in the natural world trains the brain in a different way than soccer or ballet or school or books or...gaaah...video games. It's necessary, it's how we're wired.

Some cool links... click the pics.

|

Increasingly, children's books are where the wild things aren't: A new study has found that over the last several decades, nature has increasingly taken a back seat in award-winning children's picture books -- and suggests this sobering trend is consistent with a growing isolation from the natural world.

No More "Nature-Deficit Disorder"The "No Child Left Inside" movement. In "Last Child in the Woods," I described what I called "nature-deficit disorder." I hesitated (briefly) to use the term; our culture is overwrought with medical jargon. But we needed a language to describe the change, and this phrase rang true to parents, educators, and others who had noticed the change. Nature-deficit disorder is not a formal diagnosis, but a way to describe the psychological, physical and cognitive costs of human alienation from nature, particularly for children in their vulnerable developing years. Richard Louv

Mr. RICHARD LOUV (Author, "Last Child in the Woods"): Our kids are actually doing what we told them to do when they sit in front of that TV all day or in front of that computer game all day. The society is telling kids unconsciously that nature's in the past. It really doesn't count anymore, that the future is in electronics, and besides, the bogeyman is in the woods.

|

|

SCREEN-TIME AND NATURE DEFICIT DISORDERLeaving "no child indoors" might reduce myopia---in kids' eyes and their consciousness.

The New York Times put it in blunter terms: if your kids are awake, they’re probably online. It means far less time spent outdoors. One big question is whether kids reared on virtual reality—cooped up indoors—grow into adults who care less about environmental protection and stewardship. Are we raising a generation of kids who just won’t care? |

Header: my photo of the World Famous Saltwater Cowboys driving wild ponies down the streets of Chincoteague Island VA. The (spotty butt) horse on the left is an Appaloosa, aka; App.